(c) Jack Ballard

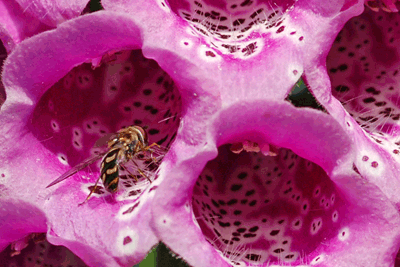

In our culture, people hold two primary associations with bees: stings and honey. In fact, neither are so closely related to bees as most people imagine. While nearly every species of bee is capable of delivering a sting, under normal circumstances bees are highly docile. Only when squeezed or directly harmed will the average bee thrust its stinger into the hide of a human. Threaten the hive, and a whole swarm of bees may sting you. Other than those two instances, bees would much rather go about their business than prick people. Many stings attributed to bees actually come from wasps which are much more aggressive and far more likely to sting with minimal provocation.

Honey comes from bees. However, most people fail to realize that very few species actually produce it. The European honey bee has been widely domesticated and accounts for most of our nation’s honey production. Of all the other species of bees inhabiting the world, just a handful of them make honey.

How many kinds of bee are there? The number and variety are astounding. Some 20,000 different species of bees buzz the planet, existing on every continent except for Antarctica. From coastal lowlands to barren mountaintops, bees make their home in every type of habitat that nurtures plants requiring insects for pollination. In size, bees range from tiny workers of the trigona minima species who barely exceed 1/16 of an inch to females of the megachile pluto species who can reach lengths slightly exceeding 1.5 inches. Bees range in color from muted blacks and grays, to red, yellow, orange and metallic hues of green and blue. Not all bees rely on pollen and nectar for sustenance. Some glean floral oils from plants. Vulture bees, a species of stingless bees, feed on dead animals.

Diverse in size and feeding habits, bees also exhibit a wide range of social structures. Most people have some elementary understanding of the complex relationships of bees in a honey-producing hive. A hive of honey bees may contain up to 40,000 bees, with the queen producing 1,000 to 2,000 eggs per day to replace worker bees lost to predators while foraging and those dying of old age. However, there are many forms of bees that exist in colonies containing a few dozen to a few hundred individuals. Bumblebee colonies typically contain around 50 to 200 bees in August or early September when their population is at its highest. Still other species of bees are loners, not forming colonies at all. The females of these types of bees, known as solitary bees, make nests in holes in the ground, decaying wood or the hollows of reeds. They often specialize in collecting the pollen of a particular plant or a single type of plant, such as sunflowers. Some species of bees are parasitic, laying their eggs in the colonies of others or even killing the resident queen and forcing the workers of the deposed matriarch to rear their young.

Whether solitary or living in a colony with thousands of members, bees perform a critical role in maintaining life on earth for a bewildering array of plants and the creatures (including humans) who consume them. Bees are the most important pollinator of flowering plants on the earth. When foraging for pollen or nectar, bees transfer pollen from flower to flower, facilitating reproduction. Scientists estimate that over 30% of the food consumed by humans is garnered from plants requiring insects for pollination, most of which is accomplished by bees.

However, worldwide populations of bees are declining dramatically. In the 35 year period from 1970 to 2005, most of the wild honey bee colonies in the United States were wiped out due to pesticides, urbanization, parasites and disease. Very few wild honey bee colonies now exist in our country. In 2006 and 2007, a dramatic drop in bee numbers, both domestic and untamed, sparked a great deal of alarm among biologists in the United States. Labeled “colony collapse disorder,” this unprecedented decline in bee numbers caused a great deal of warranted concern among crop and vegetable growers, regarding the ability of their crops to be effectively pollinated without bees. Some researchers now believe a fatal combination of a fungus and a virus was responsible for this colossal collapse in the bee population. Bee numbers continue to decline. Pesticides applied for the control of other harmful insects often exterminate bees as well, including bumblebees and other solitary species that play an important role in pollinating many flowering plants. Increasingly, domestic honey bee colonies are moved about the country, not so much for their own good, but for the pollination of crops and flowers.

Of the solitary bees, many species are stingless or only willing to sting in extreme cases of self-defense. Communal bees, such as honey bees, are also reluctant to sting, but may become quite aggressive when defending their hive. When they sting, these bees release a pheromone, a chemical substance detected by others bees which causes them to join the attack on the aggressor, either stinging it to death or driving it from the hive.

Stinging a human is generally fatal to the bee. Bees’ stingers are more suited for battle with other bees than humans or other skinned mammals. When a bee stings a human, barbs on the stinger cause it to become so firmly embedded in the skin that the bee cannot pull it free. Instead, a sizeable chunk of the bee’s hide is left behind with the stinger when it retreats after imparting the sting, a wound which is almost inevitably fatal.

Thus, the idea that bees can sting only once applies quite accurately to their painful interactions with humans and other mammals, but isn’t true of aggressive interactions between bees or between bees and other insects.

One of the bulkiest bees in America is the bumblebee. An important pollinator, bumblebees are often seen buzzing around suburban vegetable and flower gardens. Their flight has been characterized in song, and also described as defying the laws of flight. While bumblebees’ aerial antics are certainly worthy of a melody, the supposed theoretical prohibitions on their flight are in error. The idea that bumblebees are theoretically incapable of flight probably stems from a book by French scientists published in the 1930s where the authors applied principles of fixed-wing flight to the bees. More recent analysis shows that bumblebees use exceedingly fast, irregular and rotational wing movements which generate sufficient lift and propulsion for their buzzing, erratic patterns of flight.

Often misunderstood, bees are an integral strand in the complex web of biological interactions that maintain life on earth. Encountering a bee in the garden or camp isn’t a cause for alarm, but an opportunity to consider their critical connection to human life and our need to maintain a planet hospitable to our buzzing benefactors.